The Battle of Ramnagar (sometimes referred to as the Battle of Rumnuggur) was fought on 22 November 1848 between British East India Company and Sikh Empire forces during the Second Anglo-Sikh War. The British were led by Sir Hugh Gough, while the Lahore Army were led by Raja Sher Singh Attariwala. The Lahore Army’s repelled an attempted British surprise attack.

Battle of Ramnagar (Part of the Second Anglo-Sikh War)

Date:-22 November 1848

Location :-Ramnagar, Gujranwala district, Punjab

Result :- Lahore Empire victory (British cavalry repulsed with heavy losses).

Belligerents :- Sikh Empire Vs East India Company

Commanders and leaders :- Raja Sher Singh Attariwala Vs Sir Hugh Gough

Strength :- 10,000 With 20 guns Vs 15,000 With 50 guns

Casualties and losses:- 22 killed and 15 wounded Vs 26 killed 59 wounded

Background :-

Following the Lahore Empire defeat in the First Anglo-Sikh War, British Commissioners and Political Agents had effectively ruled the Punjab, using the Lahore Empire Army to maintain order and implement British policy. There was much unrest over this arrangement and the other galling terms of the peace treaty, not least within the Khalsa which believed it had been betrayed rather than defeated in the first war.

The second war broke out in April 1848, when a popular uprising in the city of Multan forced its ruler, Dewan Mulraj, into rebellion. The British Governor-General of Bengal, Lord Dalhousie, initially ordered only a small contingent of the Bengal Army under General Whish to suppress the outbreak (partly for reasons of economy, and partly to avoid a major campaign during the Hot Weather and Monsoon seasons). He also ordered several detachments of the Khalsa to reinforce Whish. The largest detachment, of 3,300 cavalry and 900 infantry was commanded by Sardar (General) Sher Singh Attariwalla. Several junior Political Agents viewed this development with alarm, as Sher Singh’s father, Chattar Singh Attariwala, the Governor of Hazara to the north of the Punjab, was openly plotting rebellion.

On 14 September, Sher Singh rebelled. Which was forced to raise the siege of Multan and retire. Nevertheless, Raja Sher Singh Attariwala and Mulraj (the Hindu ruler of a largely Moslem city-state) did not join forces. The two leaders conferred at a temple outside the city, where both prayed and it was agreed that Mulraj would supply some funds from his treasury, while Sher Singh moved north to join his forces with those of his father. This was not immediately possible, as Chattar Singh’s army was confined to Hazara by Moslem tribesmen fighting under British officers. Instead, Sher Singh moved a few miles north and began fortifying the crossings of the Chenab River, while awaiting developments. His army was swelled by deserters from those regiments of the Khalsa which had not yet rebelled, and by discharged former soldiers.

Battle :-

By November, the British had at last assembled a large army on the frontier of the Punjab, under the Commander-in-Chief, General Sir Hugh Gough. Gough had been criticised for his unvarying frontal attacks during the First Anglo-Sikh War, which had led to heavy British casualties and some near disasters.

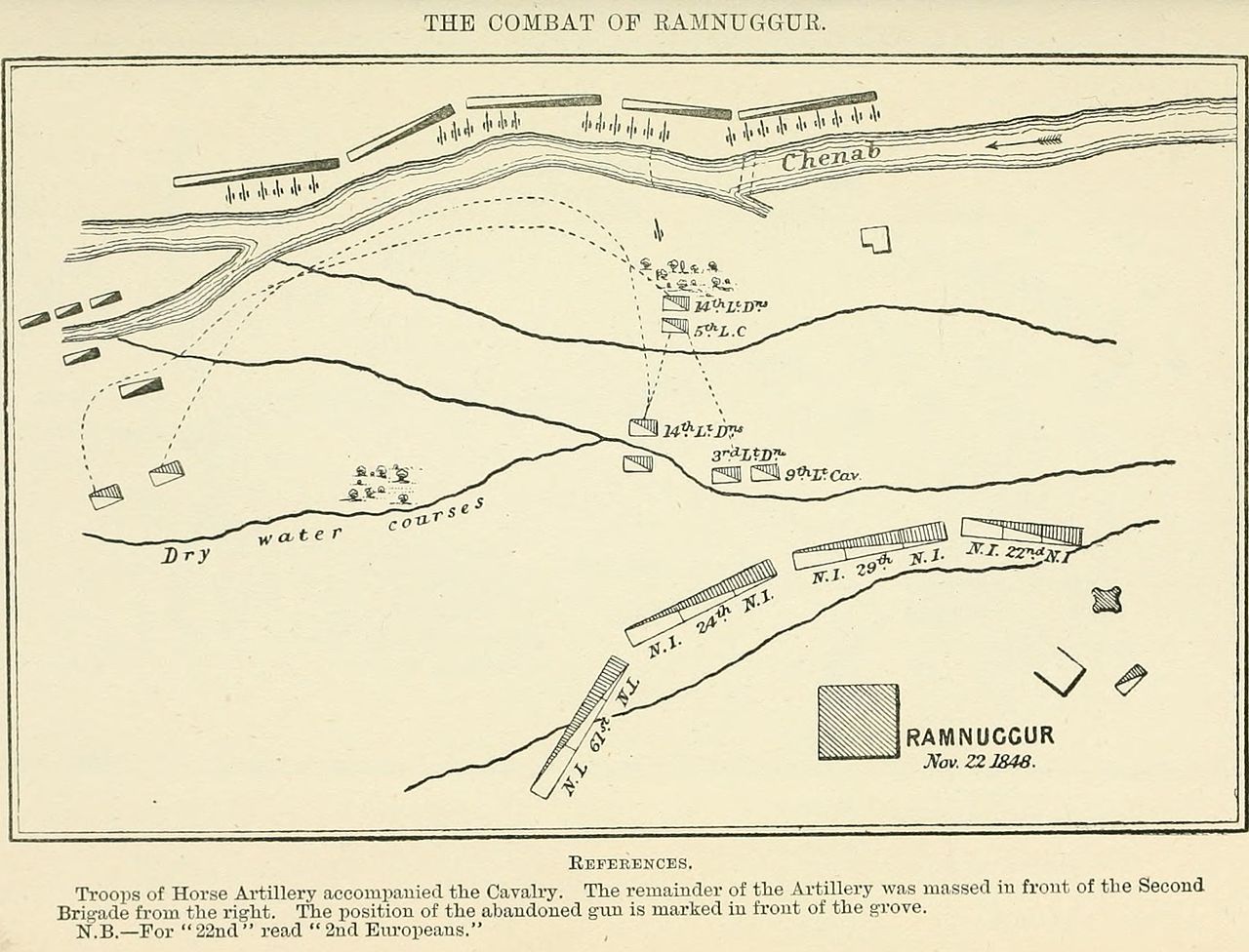

In the early hours of the morning of 22 November, Gough ordered a force of cavalry and horse artillery, with a single infantry brigade, to move to the Chenab crossing near Ramnagar (In present day Pakistan), apparently intending to capture the position by surprise. The Sikhs occupied strong positions on both banks of the river and on an island in mid-stream. The river was only a narrow stream, but the wide bed it occupied during the monsoon season was treacherous soft sand, in which cavalry and artillery could become bogged down.

At dawn, the British force assembled opposite the fords. The 3rd Light Dragoons and 8th Bengal Light Cavalry drove some Sikhs back across the river from positions on the east bank. At this point, hitherto concealed Sikh batteries opened fire. The British cavalry had difficulty extricating themselves from the soft ground. Gough’s horse artillery was outgunned and forced to retire, leaving behind a 6-pounder gun which had become bogged down.The brigade commander, Sir Colin Campbell, called up troops to retrieve the gun but was over-ruled by Gough.

Sher Singh sent 3,000 horsemen across the fords to take advantage of the British check. Gough ordered the main body of his cavalry (the 14th Light Dragoons and the 5th Bengal Light Cavalry) to attack them. These drove back the Sikh horsemen but as they pursued them down the river bank, they were hit by heavy artillery fire. The Lahore Empire cavalry also turned about and hit the 5th Light Cavalry, causing heavy casualties.

The Commanding Officer of the 14th Light Dragoons, Colonel William Havelock, led another charge, apparently without orders.He and his leading troopers were surrounded and cut down. After a third charge failed, Brigadier Charles Robert Cureton, the commander of the cavalry division to which the troops belonged, galloped up and ordered a retreat. He himself was then killed by musket fire.

Results :-

Official British casualties, including Brigadier General Cureton, were 26 killed or missing, 59 wounded. This may have referred to the 14th Light Dragoons only. Sikh casualties were not recorded.

Sher Singh had skillfully used every advantage of ground and preparation. Although the Sikh forces had been driven from their vulnerable positions on the east bank of the Chenab, their main positions were intact, they had undoubtedly repulsed a British attack, and the morale of Sher Singh’s army was boosted.

On the British side, several shortcomings were obvious. There had been little reconnaissance or other attempts to gain information on the Sikh dispositions. Gough and Havelock had both ordered foolish or reckless charges. Cureton had a reputation from the First Sikh War as a steady and capable officer, and ought to have been in command from the start.

Order of battle :-

- British regiment

- 3rd King’s Own Light Dragoons

- 9th Queen’s Royal Light Dragoons (Lancers)

- 14th the King’s Light Dragoons

- 24th Foot

- 29th Foot

- 61st Foot

- British Indian Army regiments

- 1st Bengal Light Cavalry

- 5th Bengal Light Cavalry

- 6th Bengal Light Cavalry

- 9th Bengal Light Cavalry

- 2nd European Light Infantry

- 6th Bengal Native Infantry

- 15th Bengal Native Infantry

- 20th Bengal Native Infantry

- 25th Bengal Native Infantry

- 30th Bengal Native Infantry

- 31st Bengal Native Infantry

- 36th Bengal Native Infantry

- 45th Bengal Native Infantry

- 46th Bengal Native Infantry

- 56th Bengal Native Infantry

- 69th Bengal Native Infantry

- 70th Bengal Native Infantry

References :-

- Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of Modern India, 1707 A. D. to 2000 A. D. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors.

- Farwell, Byron (1973). Queen Victoria’s Little Wars. Wordsworth Military Library.

- Dupuy, Richard Ernest; Dupuy, Trevor Nevitt (1993). The Harper encyclopedia of military history: from 3500 BC to the present. Harper Collins.

- Greenwood, Adrian (2015). Victoria’s Scottish Lion: The Life of Colin Campbell, Lord Clyde. UK: History Press. p. 496.

- Hunter, William Wilson (1881). The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Trübner. p. 542.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004). The Victorians at war, 1815-1914: an encyclopedia of British military history (illustrated ed.)